münchausen online

Anyone following her updates online could see that Mandy Wilson had been having a terrible few years. She was diagnosed with leukaemia at 37, shortly after her husband abandoned her to bring up their five-year-old daughter and baby son on her own. Chemotherapy damaged her immune system, liver and heart so badly she eventually had a stroke and went into a coma. She spent weeks recovering in intensive care where nurses treated her roughly, leaving her covered in bruises.

Mandy was frightened and vulnerable, but she wasn't alone. As she suffered at home in Australia, women offered their support throughout America, Britain, New Zealand and Canada. She'd been posting on a website called Connected Moms, a paid online community for mothers, and its members were following every detail of her progress – through updates posted by Mandy herself, and also by Gemma, Sophie, Pete and Janet, Mandy's real-life friends, who'd pass on news whenever she was too weak. The virtual community rallied round through three painful years of surgeries, seizures and life-threatening infections. Until March this year, when one of them discovered Mandy wasn't sick at all. Gemma, Sophie, Pete and Janet had never existed. Mandy had made up the whole story.

Mandy is one of a growing number of people who pretend to suffer illness and trauma to get sympathy from online support groups.

via The Guardian.

Jeanette Navarro is one of the few fakers who's prepared to talk about what she did. She's 24 and runs an online business from her home in the Philippines. She describes herself as an outcast, alienated from her family, with few friends. Jeanette does have a real medical condition – a rare autoimmune deficiency – but when she joined a worldwide online support group for fellow patients in 2008, she found herself exaggerating her symptoms and fabricating other personas to draw attention to herself.

"I was good at first. I didn't lie then," she says. "Everyone felt for me. Everyone was very sympathetic. It felt wonderful." Somewhere along the way, she says, she got "lost" amid the affection the group showed her. "I have never felt more loved and cared for in my entire life. I suddenly craved everyone's attention." After two months, she fell genuinely ill and took a break from the site for couple of weeks. "When I went back online, I found people were looking for me. That's when I posted as another person and told the group Jeanette was in a coma."

Her first lie was met with a deluge of compassion. Jeanette became intoxicated. "It made me feel so good, spending time with people who genuinely cared for me, even if they didn't know I was a fake." Once Jeanette started to lie, she found she couldn't stop. She'd spend 15-20 hours online a day, answering the 50 or so emails that arrived from concerned well-wishers, and ultimately invented five different characters to embellish and sustain the deception if attention moved away from her.

fareed zakaria on america

I am an American, not by accident of birth but by choice. I voted with my feet and became an American because I love this country and think it is exceptional. But when I look at the world today and the strong winds of technological change and global competition, it makes me nervous. Perhaps most unsettling is the fact that while these forces gather strength, Americans seem unable to grasp the magnitude of the challenges that face us. Despite the hyped talk of China's rise, most Americans operate on the assumption that the U.S. is still No. 1. But is it? Yes, the U.S. remains the world's largest economy, and we have the largest military by far, the most dynamic technology companies and a highly entrepreneurial climate. But these are snapshots of where we are right now. The decisions that created today's growth — decisions about education, infrastructure and the like — were made decades ago. What we see today is an American economy that has boomed because of policies and developments of the 1950s and '60s: the interstate-highway system, massive funding for science and technology, a public-education system that was the envy of the world and generous immigration policies. Look at some underlying measures today, and you will wonder about the future.

The following rankings come from various lists, but they all tell the same story. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), our 15-year-olds rank 17th in the world in science and 25th in math. We rank 12th among developed countries in college graduation (down from No. 1 for decades). We come in 79th in elementary-school enrollment. Our infrastructure is ranked 23rd in the world, well behind that of every other major advanced economy. American health numbers are stunning for a rich country: based on studies by the OECD and the World Health Organization, we're 27th in life expectancy, 18th in diabetes and first in obesity. Only a few decades ago, the U.S. stood tall in such rankings. No more. There are some areas in which we are still clearly No. 1, but they're not ones we usually brag about. We have the most guns. We have the most crime among rich countries. And, of course, we have by far the largest amount of debt in the world.

via TIME.

sabbath, unplugged

Google Inc. suffered a critical communications disruption that lasted around 24 hours late last month: On the evening of Feb. 25, co-founder Sergey Brin switched off his cell phone.

Unlike the recent Gmail snafu, this particular downtime was planned. Brin's wife, 23andme Inc. co-founder Anne Wojcicki, was hosting a dinner at Hidden Villa in Los Altos, in advance of the National Day of Unplugging, during which the hyper-connected are encouraged to take a day off from technology.

Wojcicki is a board member of a Jewish nonprofit that developed the annual occasion, which begins at sundown tonight and ends sundown Saturday. She held the gathering in advance to encourage people to talk about the role of technology in their lives and take a practice run at unplugging.

"People here are so connected and they're really living their lives online," she said. "I thought it'd be a good idea to see if you can disconnect for the full 24 hours."

Reboot, a New York group focused on updating Jewish traditions to make them more relevant to modern life, created the National Day of Unplugging last year to encourage people to reconnect with the real world.

Though people of all backgrounds are encouraged to participate, the concept was inspired by the Sabbath in Jewish tradition, a weekly day of rest. Reboot devised a "Sabbath Manifesto" that included 10 goals for the day, such as: avoid technology, connect with loved ones, get outside and drink wine. Participants can draw that technology line wherever they please, from light switches to cars to televisions.

via SFGate.

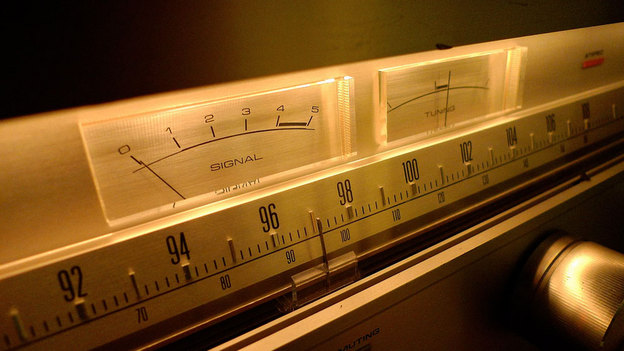

once upon an audiophile...

You may remember the type: Laid-back in an easy chair, soaking in Rachmaninoff, Reinhardt or the Rolling Stones, enveloped by the very best, primo, top-of-the-line stereo equipment an aficionado could afford.

In robot-like, 1980s cadence, the audiophile could rattle off favorite components, which might include an all-tube Premier One power amp by conrad-johnson, a Sota Sapphire turntable, an Ortofon MC-2000 cartridge and a pair of Magneplanar speakers.

Geeky? Mos def.

But the audiophile was a symbol of the Golden Age of Audiophonics, a time when certain people worshiped at the altar of expensive high-fidelity, two-channel stereo equipment. They were knights errant on an eternal quest for audio perfection — the exact replication of an original performance.

Here is the way one New York Times writer described a Holy Grail system in 1980: "There is a greater transparency of orchestral textures, giving each instrument an almost tactile presence." The theological debates pitted vacuum-tube amplification advocates against those preferring solid state, or transistorized, amplification. The sacred texts were magazines such as Stereo Review and High Fidelity. Stereo stores were the holy shrines.

Then came the barbaric revolution. The boombox, the Walkman and other hand-held devices made music more portable. Digital sound enabled listeners to store scads of compressed, easy-to-download music files — first on computers, then on miniature devices and cell phones. Quality in recordings was sacrificed for speed and convenience. Loudness became more important than clarity. The richness and warmth of a recording was replaced by tinniness and splash.

Now it's 2011. And amid all the earbudded iPods, smart phones and MP3 players, one can't help but wonder: Whatever happened to the audiophile?

feynman post-burnout

Then I had another thought: Physics disgusts me a little bit now, but I used to enjoy doing physics. Why did I enjoy it? I used to play with it. I used to do whatever I felt like doing - it didn't have to do with whether it was important for the development of nuclear physics, but whether it was interesting and amusing for me to play with. When I was in high school, I'd see water running out of a faucet growing narrower, and wonder if I could figure out what determines that curve. I found it was rather easy to do. I didn't have to do it; it wasn't important for the future of science; somebody else had already done it. That didn't make any difference. I'd invent things and play with things for my own entertainment. So I got this new attitude. Now that I am burned out and I'll never accomplish anything, I've got this nice position at the university teaching classes which I rather enjoy, and just like I read the Arabian Nights for pleasure, I'm going to play with physics, whenever I want to, without worrying about any importance whatsoever.

Within a week I was in the cafeteria and some guy, fooling around, throws a plate in the air. As the plate went up in the air I saw it wobble, and I noticed the red medallion of Cornell on the plate going around. It was pretty obvious to me that the medallion went around faster than the wobbling.

I had nothing to do, so I start to figure out the motion of the rotating plate. I discover that when the angle is very slight, the medallion rotates twice as fast as the wobble rate - two to one [Note: Feynman mis-remembers here---the factor of 2 is the other way]. It came out of a complicated equation! Then I thought, ``Is there some way I can see in a more fundamental way, by looking at the forces or the dynamics, why it's two to one?''

I don't remember how I did it, but I ultimately worked out what the motion of the mass particles is, and how all the accelerations balance to make it come out two to one.

I still remember going to Hans Bethe and saying, ``Hey, Hans! I noticed something interesting. Here the plate goes around so, and the reason it's two to one is ...'' and I showed him the accelerations.

He says, ``Feynman, that's pretty interesting, but what's the importance of it? Why are you doing it?''

``Hah!'' I say. ``There's no importance whatsoever. I'm just doing it for the fun of it.'' His reaction didn't discourage me; I had made up my mind I was going to enjoy physics and do whatever I liked.

I went on to work out equations of wobbles. Then I thought about how electron orbits start to move in relativity. Then there's the Dirac Equation in electrodynamics. And then quantum electrodynamics. And before I knew it (it was a very short time) I was ``playing'' - working, really - with the same old problem that I loved so much, that I had stopped working on when I went to Los Alamos: my thesis-type problems; all those old-fashioned, wonderful things.

It was effortless. It was easy to play with these things. It was like uncorking a bottle: Everything flowed out effortlessly. I almost tried to resist it! There was no importance to what I was doing, but ultimately there was. The diagrams and the whole business that I got the Nobel Prize for came from that piddling around with the wobbling plate.

via ~kilcup.

red / blue premarital sex

Blues also suffer more often from a problem very difficult to quantify: confusion. If you believe pornography and cohabitation and premarital sex are wrong, then you will likely feel guilty when you misstep, but at least you know where you stand. Liberals have a hard time articulating what they in fact believe about sex, tending to fall back on a radical tolerance that does not always square well with the emotional weight of the matter. Lacking a well-defined ethical structure to understand sexual choices, blues seem to wish away the idea that such a structure might be worth having. (“It’s up to you to decide. Just use protection.”) But as Regnerus and Uecker show, sexual regret is a common phenomenon, arising even from mutual and safe hookups. Some 70 percent of young adults, in one study, think they should have waited longer to lose their virginity. And in a national college survey, nearly as many men as women—73 percent of them—regretted at least one hookup.

Reds who look back on sex they are sorry they had, the authors observe, often describe it as an aberration that does not alter their fundamental outlook; the broken rule remains in effect. But if you are a blue who does not believe in “moral rules” about sex, then a cringe-inducing sexual encounter leaves you to wonder why you are cringing. If God is dead and premarital abstinence is an antiquated idea, the source of such regret is mysterious and therefore tough to address. Regnerus and Uecker have not set out to construct a new sexual ethics, and anyone who does so in public tends to take a beating. But this book, which offers a wide-ranging guide to where we are now, could occasion some thinking about where we want to be.

via The New Republic.

125

One morning in early January, David Murdock awoke to an unsettling sensation. At first he didn’t recognize it and then he couldn’t believe it, because for years — decades, really — he maintained what was, in his immodest estimation, perfect health. But now there was this undeniable imperfection, a scratchiness and swollenness familiar only from the distant past. Incredibly, infuriatingly, he had a sore throat. “I never have anything go wrong,” he said later. “Never have a backache. Never have a headache. Never have anything else.” This would make him a lucky man no matter his age. Because he is 87, it makes him an unusually robust specimen, which is what he must be if he is to defy the odds and maybe even the gods and live as long as he intends to. He wants to reach 125, and sees no reason he can’t, provided that he continues eating the way he has for the last quarter century: with a methodical, messianic correctness that he believes can, and will, ward off major disease and minor ailment alike.

via NYTimes.com.