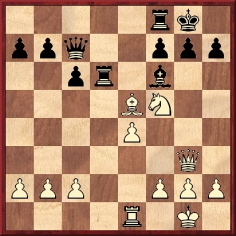

attack

Leonid Alexandrovich Shamkovich vs BlohmUSA 1977 Spanish Game: Berlin Defense. Rio Gambit Accepted

via ChessGamnes.com.

no more draws

Rustam Kasimdzhanov:

We need a result. Every single day.

And here is how it works. We play classical chess, say with a time control of four to five hours. Draw? No problem – change the colours, give us 20 minutes each and replay. Draw again? Ten minutes each, change the colours and replay. Until there is a winner of that day. And the winner wins the game and gets one point and the loser gets zero; and the game is rated accordingly, irrelevant of whether it came in a classical game, rapid or blitz.

via ChessBase.com.

That sounds wonderful!

capablanca

Simply beautiful!

Jose Raul Capablanca vs Professor Marc Fonaroff New York 1918 Spanish Game: Berlin Defense. Hedgehog Variation

via ChessGames.com.

More, at ChessHistory.com

alekhine's pawn

In C.N. 3369 Yasser Seirawan (Amsterdam) reported that Najdorf had told him a similar story about playing Alekhine, but with some different details:

‘The Polish club, he claimed, deliberately annoyed Alekhine by announcing that only 20 players had paid for the privilege to participate, and Alekhine insisted on being paid the agreed fee despite having only half the field. Reluctantly, the club directors agreed and proposed that Alekhine play ten games by sight and ten blindfold. Alekhine agreed. The club then snuck all the best players into the blindfold room and put ten patzers on the games that Alekhine could view. Just as the club directors had contrived, Alekhine had a terrible time. He wiped out the players he could see and sat racking his brains on the blindfold games, where the masters were in ambush.

Concerning his own game, Najdorf told me he was on the black side of a Sicilian in which the players had castled on opposite wings. Alekhine was breaking through when Najdorf uncorked the standard …Rc8xc3 exchange sacrifice. Alekhine had seen that shot and did not bother to recapture the rook, pursuing his own attack instead. The move he had missed was the follow-up …Rc3xa3, and Najdorf’s attack was first and decisive.

Najdorf added that many years later he had hosted Alekhine in a drinking bout in Buenos Aires. They both got thoroughly drunk. In a toast Najdorf declared Alekhine the greatest chess player ever but added, “Just remember: our score is one draw and one win in my favor”. Alekhine maintained that even if drunk he knew that their score was one draw. Najdorf then reminded Alekhine of the Polish display, and Alekhine said, “Are you the one who gave me …Rxa3?” Najdorf was astounded at Alekhine’s memory, even when he was intoxicated.’

via chessgames.com.

bobby fischer

The tortured genius and the celebrity recluse are two archetypes by which the popular imagination appears incurably enthralled. They occupy extreme but ambiguous positions in the social firmament, simultaneously familiar and unknowable, often winning our sympathy even as they fail our understanding. Working as Mephistophelean morality tales, they reassuringly remind us that exceptional talent can be an affliction as well as a gift and that sometimes the price of success is one that we – the average, the normal, the unchosen – would not wish to pay. No one in recent times has combined these two roles with more tragedy or pathos than Fischer.His descent into wild and irrational behaviour is far from a unique narrative, particularly in chess. The history of the game contains many similar trajectories. As GK Chesterton noted in arguing that reason bred insanity: "Poets do not go mad, but chess players do." Akiba Rubinstein, the early 20th-century Polish grandmaster, would hide in the corner of the competition hall between moves, owing to his anthropophobia (fear of people), retiring from the game when schizophrenia got the better of him. William Steinitz, the Austrian who was the world's first undisputed chess champion, died in an asylum. Then there was Paul Morphy, the American who was said to be the 19th-century's finest player and to whom Fischer has frequently been compared: he quit the game, having beaten all his rivals, and began a decline into paranoid delusion. Aged 47, he was found dead in his bath, surrounded by women's shoes.

via The Observer.

"The thing that strikes me about Fischer's chess," Short says, "is that it's very clear. There are no mysterious rook moves or obscure manoeuvrings. He's very direct. There's a great deal of logic to the chess. It's not as though it's not incredibly difficult – it is incredibly difficult. It's just that when you look at it you can understand it – afterwards. He just makes chess look very easy, which it isn't."